The Trust Deficit: Why Good Governance Depends on More Than Institutional Design

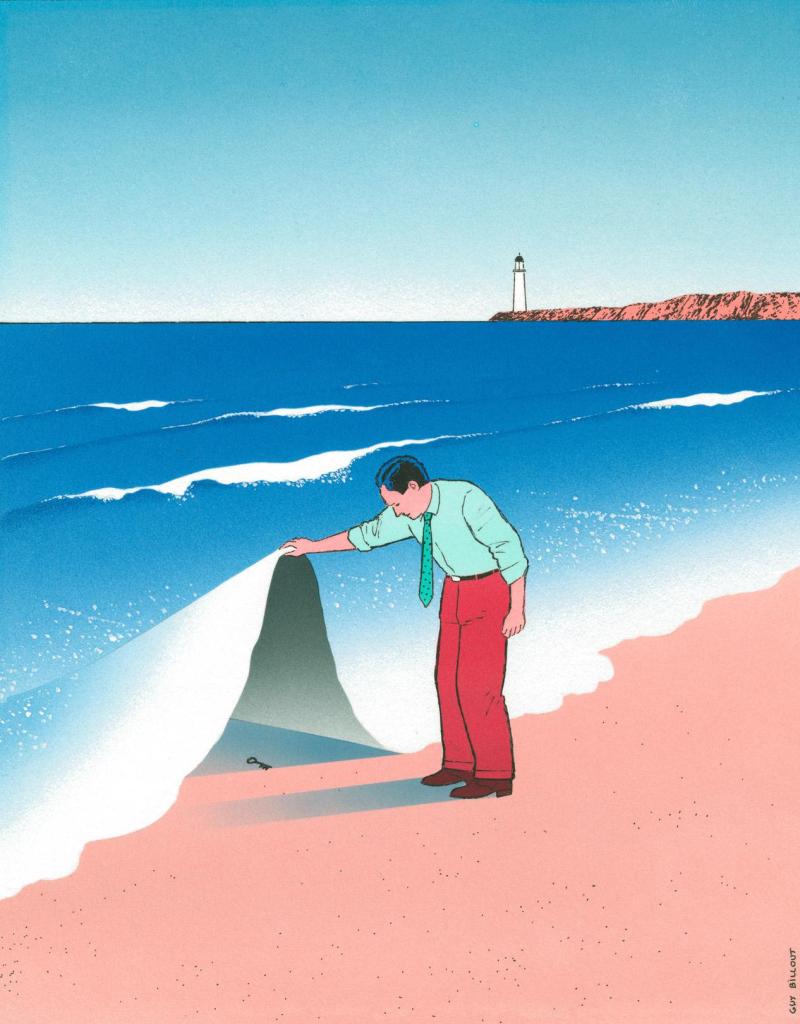

Introduction We measure everything that makes societies succeed, GDP, inflation, stock prices, even consumer sentiment. Yet we almost never measure trust. Perhaps that’s because trust refuses to be quantified. It’s intangible, shifting, and deeply human. Economists can chart growth; sociologists can map institutions. But the quiet faith that citizens place in those institutions or withdraw from them, is far harder to capture. Trust is layered and uneven. We trust our friends differently than our bosses, our bosses differently than our politicians. Even among peers, trust fluctuates, shaping how we cooperate, share, and believe. If it’s this complex between individuals, imagine its fragility at the scale of nations. That fragility is showing. Across the world, citizens are losing faith in the institutions that were once the anchors of public life. Governments, media, and even the private sector now face a legitimacy deficit that no constitutional reform or policy tweak can easily fix. Why does this matter? Because trust is the invisible infrastructure of governance. Without it, the most elegant institutional design fails to function. Laws are ignored, reforms stall, and participation fades. The machine of government no matter how well engineered, cannot run if its individual gears refuse to turn. What is the trust deficit? Across the world, the machinery of government is grinding. Its gears still turn, but slowly and unevenly, corroded not by age, but by the withdrawal of public trust. This corrosion is not confined to the state alone. It extends through the entire institutional ecosystem: from media to business, from education to civic life. What we are witnessing is not distrust of a government, but a collective unravelling of faith in the architecture of modern society. In the past, governments set the agenda and watched its effects ripple outward. Today, those ripples flow both ways. Corporate influence shapes public policy, online discourse shapes electoral outcomes, and the collapse of media credibility amplifies cynicism toward all authority. Institutions no longer operate in silos, they share legitimacy, and they share its loss. For governance to function now, society as a whole must remain in a state of mutual trust. Yet governments themselves have often engineered their own distrust. They relaxed lobbying rules that blurred the line between public duty and private interest. They meddled in journalism, defining what counts as acceptable truth, especially during crises like COVID-19. They let infrastructure decay while pouring budgets into war or corporate tax relief. The result is a bleak feedback loop where citizens no longer trust the state because it seems captured, and the state, sensing hostility, becomes ever more insular and defensive. The real damage lies not just in these grievances, but in the emotional fatigue beneath them. The quiet belief among citizens is that they are being punished for doing everything right. When law-abiding people feel that fairness is a losing strategy, the social contract begins to fray. Declining trust is both a symptom and a driver of that fracture. Economic anxiety feeds mistrust, and mistrust deepens economic stagnation [1]. Why institutional design isn’t enough Here lies the paradox of institutional trust. We assume that if an institution is designed efficiently, it will deliver faithfully. We build systems founded on ideals of integrity and competition, and in doing so, we begin to view politics like a marketplace, one where rival interests supposedly refine the product until it performs perfectly. But this faith in self-correction is misplaced. Inefficiencies, loopholes, and unintended consequences are not neutral flaws, they are opportunities for manipulation. The fixes rarely keep pace with the failures. And no matter how elegant an institution appears from the outside, what matters is how it runs. A Rolls-Royce without an engine is just a polished metal shell. In this pursuit of appearance, institutions have become obsessed with best practice rather than better outcomes. The result is a theatre of competence, glossy frameworks, performance metrics, and strategy documents that mask operational paralysis. Systems that seem functional from the outside often stall in practice, leading to drift, misuse, and directionless steering. We accept that large businesses should have a say in policymaking but rarely ask how loud that voice should be. We value truth in journalism but hesitate to install safeguards against narrative capture and neutrality. We defend electoral mandates but fail to ensure that power, once granted, remains accountable. Designing a system to look good without ensuring it works well invites exploitation. Over time, the very actors entrusted with protecting the public begin to master the system’s weaknesses instead. And when citizens see that the rules benefit insiders first, the corrosion of trust becomes complete. The psychology of political trust Even if trust cannot be precisely measured, we can still trace where it comes from. The old adage that respect is earned, not given captures the essence of our dilemma. Trust works the same way but with higher stakes. It is not a sentiment we bestow freely, it is a verdict delivered over time. In our personal and professional lives, we constantly test the people around us. We give them tasks, watch how they handle pressure, and decide, often subconsciously, whether they are dependable. Trust is a cumulative result of consistency, not a gesture of goodwill. Yet many in power still seem shocked by the public’s scepticism. They mistake the withdrawal of trust for cynicism, when in fact it is reasoned caution. Blind trust is dangerous, evolution taught us that long before politics did. Why, then, should citizens grant faith to leaders who have repeatedly broken it? The slogans of renewal such as “I’ll bring change” or “I’m different from those before me” now provoke reflex suspicion. Decades of betrayal have turned these phrases into warnings, not promises. Trust, therefore, is not the product of naïveté but of rational assessment. It must be earned through sustained action, not slogans. Governments spend vast resources proclaiming what they intend to do rather than demonstrating what they have done. The result is a politics of marketing over substance. A wiser model would narrow its ambitions